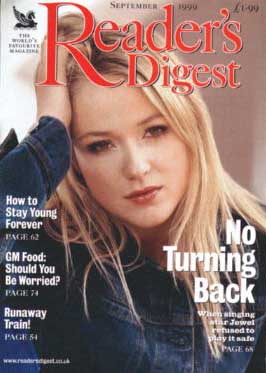

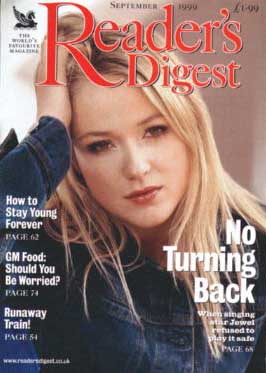

No Turning Back

No Turning Back

Suzzane Chazin

Readers Digest

Jewel Kilcher was just 18, fresh out of high school and completely unsure of

what to do with her life. She had moved from Michigan to San Diego to be

with her divorced mother and was working at a series of disappointing,

low-paying jobs--waiting tables and punching cash registers. There was

little time or money for exploring careers. In fact she was barely scrapingby.

Things only worsened when a burning began in the willowy teenager's back and

traveled all the way down her groin. Her long blond hair was damp with fever

the day she mutely followed her mother into a hospital emergency room.

It was the eighth medical facility mother and daughter had visited that hazy

spring afternoon in 1993. Three hospitals and four clinics had already

refused to treat the girl's raging kidney infection because she was broke and

lacked medical insurance.

Finally they found a doctor who would attend to her, but it was a physical

and spiritual low point. In the weeks that followed, Jewel poured out her

anxieties to her mother, Nedra Carroll. What should she do? She loved the

arts--literature, drawing, dance, music. But how could she possibly pursue

any of these demanding careers when just surviving was claiming so much of

her energy?

Nedra, in tough financial straits herself, came up with a novel solution:

they'd give up their shared apartment and move into vans near the beach.

Without the pressure to meet their rent, Jewel could focus on her life goal

and make it happen.

After searching her soul, Jewel decided that singing and songwriting meant

the most to her. But Nedra probed further, asking why.

Jewel thought about her reasons. Money? She'd always had so little; she'd

even grown accustomed to living on what she could carry in a knapsack. Fame?

She'd always felt like an outsider, so that didn't matter. The one thing

that she really cared about was her songs--inspiring people with her words

and voice. "I want to sing to remind people to live their dreams," she told

her mother.

Still, she couldn't help feeling a flicker of fear. Friends were skeptical

of her plans, and their doubts were contagious. What if she failed at the

one thing she wanted to do? Perhaps she should look for a safer way to use

her talent--singing on tour boats, for instance, or teaching grade school

music, like her dad in Alaska.

"Maybe I should have a fallback plan," she suggested to her mother.

Nedra shook her head. "If you have a fallback plan, you will fall back. You

are young. Be brave. Have faith in yourself."

So the decision was made: the two would live like frontier women on the

beach with the sound of the Pacific surf rolling in their ears. And Jewel

would put her talents and ambitions to the test.

It was not the first time either had lived such a spartan life. Nedra and

Jewel's father, Atz Kilcher, a social worker, were raised on the Alaskan

frontier. Though the Kilchers moved often when Jewel and her two brothers

were small, she spent a good part of her formative years on her Swiss

grandparents' 640-acre homestead, 225 miles southwest of Anchorage.

Frontier Child:The homestead was a place of rugged beauty, surrounded by soaring

tree-covered canyons and snow-capped mountains. But it was also isolated and

harsh, with only a coal stove for warmth and an outhouse for plumbing.

There, learning to do tough, physically demanding work, Jewel honed a spirit

of determination. Even before the move, she had shown a single-mindedmess

that impressed her family. In third grade, for instance, she was diagnosed

with dyslexia, a disability that affected her reading and coordination.

Later that year she was rejected from an after-school gymnastics program she

desperately wanted to join, because she couldn't do somersaults andcartwheels.

"That doesn't mean you can't do gymnastics," her mother told her. "It just

means you'll have to work harder."

So Jewel began practicing three hours a night until she could do the

maneuvers as well as the natural atheletes in her grade. She was accepted

into the program.

Jewel showed the same determination singing. Watching her folk-singing

parents perform, Jewel delighted in her father's yodeling and wanted to learn

how to do it herself. But her parents, fearing it would strain her

six-year-old vocal cords, were reluctant to teach her. So she practiced

relentlessly on her own until she could do it with ease.

But the young girl with the golden voice couldn't will away the most

devastating event of her childhood. When Jewel was eight, her parents

divorced. Nedra remained in Anchorage, and Atz moved to his parents'

homestead. The children spent time with both parents, but lived mainly with

their father. They took over the barn at the homestead and lived simply off

the land--bleeding birch trees to make syrup, canning vegetables, smoking and

drying salmon they caught themselves. Atz even taught the children to weave

baskets from willow roots.

He and Jewel became a singing duo. But unlike her parents' singing

engagements, some of these were in seedy taverns and veteran halls, often

reeking of smoke and spilled beer. The patrons included tattooed bikers,

drifters and women past their prime still trying to squeeze into skintight

jeans. At a biker bar in Anchorage, Jewel watched a man collapse in the

parking lot from a drug overdose. "What I saw in those places turned me off

drugs, drinking and smoking for life," she says.

She also observed firsthand what happens to people who lose their passion for

life and end up merely existing. And she vowed it would never happen to her.

Singing to the clink of shot glasses and the chatter of bar crowds taught

Jewel something she might never have learned any other way. One night,

shortly before one of their performances, she and her father got into an

argument. Already upset, Jewel broke into tears when her father reminded her

to leave her personal life behind when she went onstage. What did it matter,

she thought, since the audience consisted of just a few grizzled, drunked

veterans?

Then a man in the crowd scolded her. "Stop looking so depressed," he called

out. The words had a humbling effect. Jewel suddenly understood that her

job was to please the audience, not herself. She stopped crying and finished

the set flawlessly. And she determined never to take an audience for granted

again.By age 13, restless and wanting to spend more time with her mother, Jewel

packed up and moved in with Nedra in Anchorage. But she was no longer the

child her mother tucked into bed each night five years earlier. "I was

bitter about the divorce, angry and mistrustful when I first moved in with my

mom," explains Jewel. She developed friendships with members of street

gangs. She dated older guys. She even shoplifted a few times.

But Jewel's life took yet another new turn when a teacher from the

Interlochen Arts Academy heard her sing at a summer music festival.

Impressed by her voice, he encouranged her to apply for the prestigious arts

school. Jewel did, and won a voice scholarship. Interlochen gave Jewel

formal training in dance, writing and theater and broadened her artistic

horizons.On The Beach:

Growing up without running water water turned out to be good preparation for

living in a van beside the Pacific. Used to quick scrubdowns in Alaska's

subzero temperatures, Jewel was expert at washing her hair efficiently in

public restrooms at Kmart and Denny's. She was comfortable with thrift-shop

clothes and could get by on little more than carrots and peanut butter while

looking for work.

Eventually she found a regular spot performing at a Pacific Beach coffeehouse

called The Inner Change. While there, she wrote a song entitled "Who Will

Save Your Soul?" about those who lead lives of physical comfort but spiritual

emptiness.By the middle of 1993 Jewel was attracting overflowing crowds to the

coffeehouse and drawing the attention of record-industry talent scouts. Then

in December 1993 her shimmering voice and folk-style acoustic songs landed

her a recording contract with Atlantic Records.

Jewel might have hoped that the worst of her struggles were behind her. But

yet another round was beginning. When her first album, Pieces Of You, was

released in February 1995, it sold fewer than 500 copies a week. Her sweetly

innocent voice and uplifting songs were met with derision by the

often-cynical entertainment industry. Undeterred, Jewel traveled the country

alone, usually with only a road manager to keep her company. Back in San

Diego, her mother helped to manage her career. Jewel played mostly small

clubs, sometimes 40 concerts in 30 days, never staying more than a couple of

nights in any one city.

Worse still were some of her bookings. She would occasionally open for

heavy-metal bands with screaming electric guitars and fans wearing garish

clothes and makeup.

Once, Jewel was booked to play a black high school in Detroit. She peeked

through the curtain before the show, delighted to see a full auditorium of

excited students. But their noisy exuberance turned to boos and catcalls

when the curtain went up. They had expected a rap singer called Jewell, and

a young woman with an acoustic guitar didn't turn them on. Many of the

students walked out. Still, recalling her father's admonition years earlier,

Jewel realized it was her job to give a good show. So she sang with

undiminished passion for those who stayed.

Radio stations refused to play her. Music critics scoffed at her lack of

hipness. She was derided for everything from her crooked teeth to her

constant encoragement that fans follow their dreams. But Jewel stayed on the

road, playing coffeehouses, signing CDs in suburban stores and thanking

everyone who came to her performances.

Despite the carping of critics, more and more people took note of her talent

and charisma, and word spread about her riveting live performances. As her

fan base grew by word of mouth, the critics counted for less. By appealing

directly to those who mattered to her--those for whom she wrote the

music--Jewel ignited her career.

The decisive breakthrough came in mid-1996 when Pieces of You went gold more

than a year after its release, selling 500,000 copies. With radio stations

responding at last to her fans, the single "Who Will Save Your Soul?" climbed

the charts until it was a top-ten hit.

By the time her second CD, Spirit, was released in late 1998, Jewel had an

international following. Spirit went on to sell three million copies, and

her admirers still couldn't get enough. Soon Jewel will apear in her first

movie, a Civil War drama called Ride With the Devil. Film can only extend

her reach as a star.

All of which is a stunning journey for a young woman who was virtually

homeless just six years ago. But Jewel Kilcher understands how it happened.

In fact, she relives the converstaion with her mother that made all the

difference.

"If she'd encouraged me to have a fallback plan, I'd have made one. I was

scared. But being safe didn't mean being happy." Nedra understood this, and

so eventually did Jewel. Happiness came instead from following her

passion--and realizing there could be no turning back.